When the Allen brothers founded Houston in 1836, promising a “beautiful capital,” they overlooked one critical factor: public health. The city’s early years weren’t a heroic building project; they were a desperate struggle for survival. The nascent medical system was primitive, and the harsh climate, poor sanitation, and unknown diseases turned the settlement into a virtual graveyard. Read more about the challenging birth of the future metropolis on i-houston.com.

A Town on a Swamp: Houston’s Environmental Curse

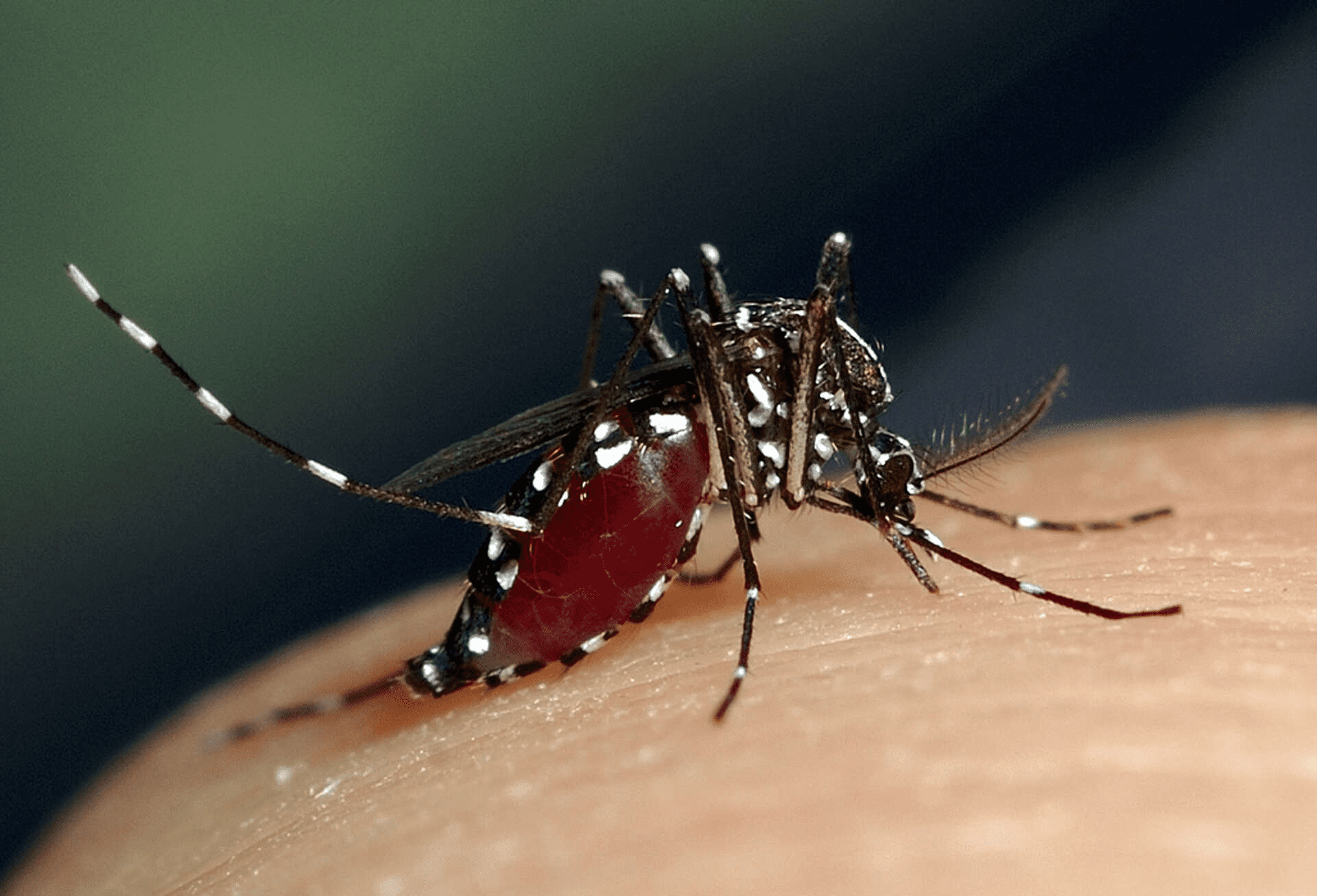

The first and most significant problem the founders of Houston faced was rooted in the city’s geography. The town was built on a low, marshy area adjacent to the Buffalo Bayou river. This landscape, ideal for port development and cotton transport, turned out to be a genuine ecological curse. The warm, humid Gulf Coast climate created perfect, year-round conditions for the proliferation of mosquitoes—the invisible enemy that spread the era’s most terrifying scourges.

The founders and early residents had absolutely no understanding of the true cause of their ailments. They clung to the erroneous “miasma theory”—the belief that diseases were caused by “putrid” or “bad air” rising from the swamps. Instead of draining the land, they often focused on futile measures. Yet, the source of their troubles was not in the vapors, but in the tiny carriers. Every mosquito bite could carry a deadly threat, turning a routine evening by the river into a fatal lottery. This swampy foundation was the determinant of frequent epidemics of Yellow Fever and Malaria, which relentlessly devastated Houston’s population throughout the entire 19th century.

The Terror of Epidemics

The medical history of early Houston is a story of repeated epidemics. Two diseases regularly decimated the population, crippling commerce and causing widespread panic:

- Yellow Fever (“Yellow Jack”). This was an annual summer curse, typically imported via maritime routes from New Orleans and Mexico. A victim could be healthy one day and die three days later from fever, jaundice, and “black vomit” (partially digested blood).

- Cholera and Malaria. Poor quality drinking water and the absence of a proper sewage system made the city vulnerable to cholera, while the swamps ensured a constant, pervasive level of malaria.

For instance, in 1853, approximately 60% of the residents in neighboring Galveston contracted Yellow Fever, illustrating the massive regional scope of the threat.

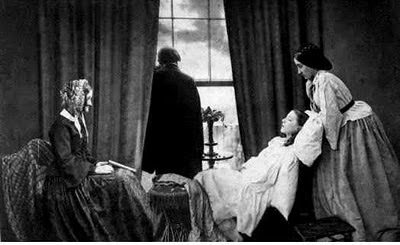

Pioneer Physicians and the State of Medicine

The first medical practitioners in the Republic of Texas, which included Houston, were far removed from modern specialization. Doctors of the era were true “jacks-of-all-trades,” often combining medical practice with military, political, or even business activities. They were mostly graduates of medical colleges in the U.S. and Europe, arriving searching for opportunities but forced to work in extremely primitive conditions. Their role extended beyond healing: they were the elite, administrators, and field surgeons.

Dr. Ashbel Smith: The Architect of Healthcare

One of the most prominent figures of this era was Dr. Ashbel Smith. His contribution was crucial to establishing public health. He was not only the Surgeon General of the Army of the Republic in 1837 but also the founder of the first military hospital in Houston. This hospital became the focal point for medical aid in the city. Smith chaired the first medical board, which was granted the authority to issue licenses to practice medicine—a critically important step to separate qualified professionals from charlatans. Smith later pursued careers as a politician, diplomat, and was even a co-founder of the University of Texas.

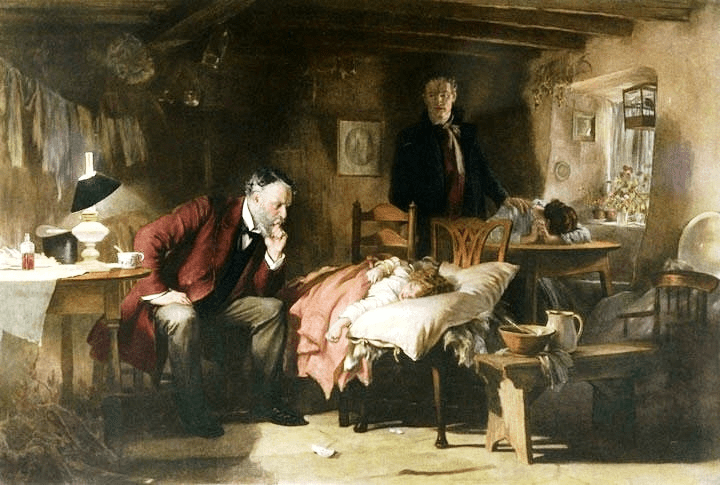

The Brutal Reality of Field Surgery

Medicine in those years was a brutal science, particularly in the context of military conflicts. Doctors involved in decisive events, like the Battle of San Jacinto (1836), faced the horrific necessity of emergency surgical interventions. Due to the absence of anesthesia, the only recourse against gangrene was often amputation.

Surgeons relied on simple but effective tools: sharp knives, saws, and for pain relief, the most available substances—alcohol and opium. Antiseptics were yet unknown. For example, Dr. Davidson Tiffany, another notable physician, described how amputations were done quickly, and infection was more common than recovery. This daily struggle against high mortality rates tested the first doctors, shaping the foundation of medical practice in Houston.

A Blend of Ancient and New: Medical Eclecticism

The medical knowledge utilized by early Houston physicians was a genuine eclectic mix, drawing from two entirely different worlds. It was a fusion of outdated European traditions and the local wisdom of indigenous tribes.

A significant part of their practice was based on medical dogma imported from colleges in the Eastern U.S., which in turn relied on European ideas that were often flawed. The theory of the four bodily humors still predominated into the 19th century, and many illnesses were treated with bloodletting and intense purging. These methods, considered “scientific,” often not only failed to help but actually depleted patients, especially those suffering from malaria or yellow fever. Surgical procedures, as we know, were performed without proper anesthesia or antisepsis, relying solely on the physician’s speed and skill.

At the same time, the pragmatism of the Texas frontier compelled doctors to seek knowledge from residents. Many adopted information from Native Americans and Mexican healers (curanderos) about the properties of local plants. If European medicines were expensive or unavailable, doctors used plants from the wild. It was often this indigenous botanical knowledge that yielded better results than the outdated academic approaches. Thus, the medical community of early Houston operated at the crossroads of scientific progress, obsolete ideas, and pragmatic folk medicine, making its practice unique but highly unpredictable.

| Method | Description and Effectiveness |

| Bloodletting | A deeply rooted European practice, thought to “cleanse” the body of “bad humors.” In reality, it typically weakened the patient. |

| Purging and Vomiting | Using drugs like calomel (mercury chloride) to “expel the sickness” from the body. This was frequently dangerous. |

| “Change of Air” | A popular but useless piece of advice—it was believed the sick should move to a “healthier” location. This actually contributed to the spread of infections. |

| Opium | Used in the form of laudanum (a tincture) to relieve severe pain, fever, and dysentery. It was the most effective symptomatic remedy available. |

From Home Remedies to Professional Licensing

In its infancy, Houston faced a critical lack of medical infrastructure, forcing residents to rely on home remedies or rudimentary treatment. The city desperately needed institutionalization, and the first steps were taken by key figures.

In 1837, the aforementioned Surgeon General Ashbel Smith established the Military Hospital—the first official treatment facility to provide any kind of organized care. That same year, recognizing the danger of unqualified practitioners, the Congress of the Republic of Texas created the Board of Medical Censors. This was the first licensing body, whose sole purpose was to distinguish qualified doctors from the numerous charlatans arriving in Texas. However, its effectiveness in the sparsely populated region was quite limited.

Given the high cost of services from licensed doctors and the often-questionable efficacy of their outdated methods, the Houston community actively sought alternatives. Many residents preferred homeopathy, hydropathy, or simple “grandma’s recipes.” The market was flooded with so-called patent medicines—brightly colored bottles and powders sold with promises of instant cures for all possible ailments. However, these remedies, often advertised as a panacea, usually contained nothing more than large doses of opiates and alcohol, providing only temporary relief, not a cure. This was an era when the absence of quality healthcare and the proliferation of dubious “cures” made survival in Houston not just a matter of entrepreneurial spirit, but a true gamble.