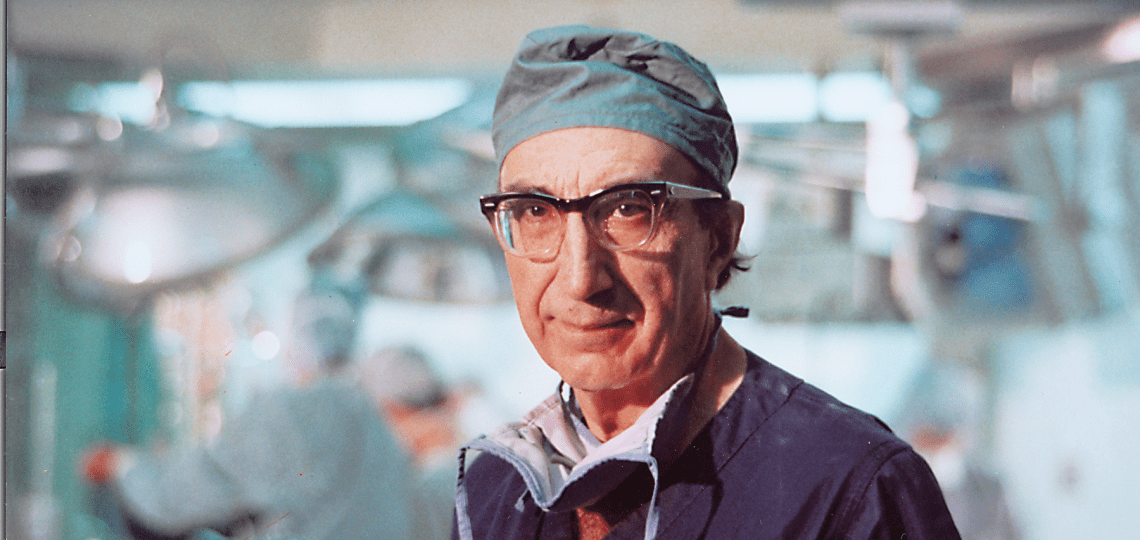

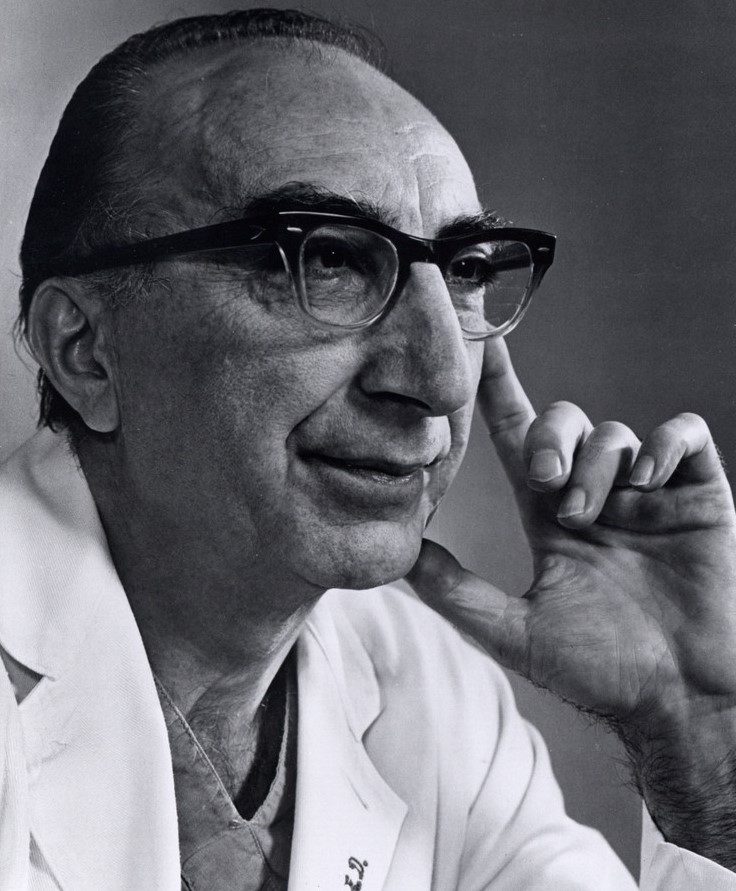

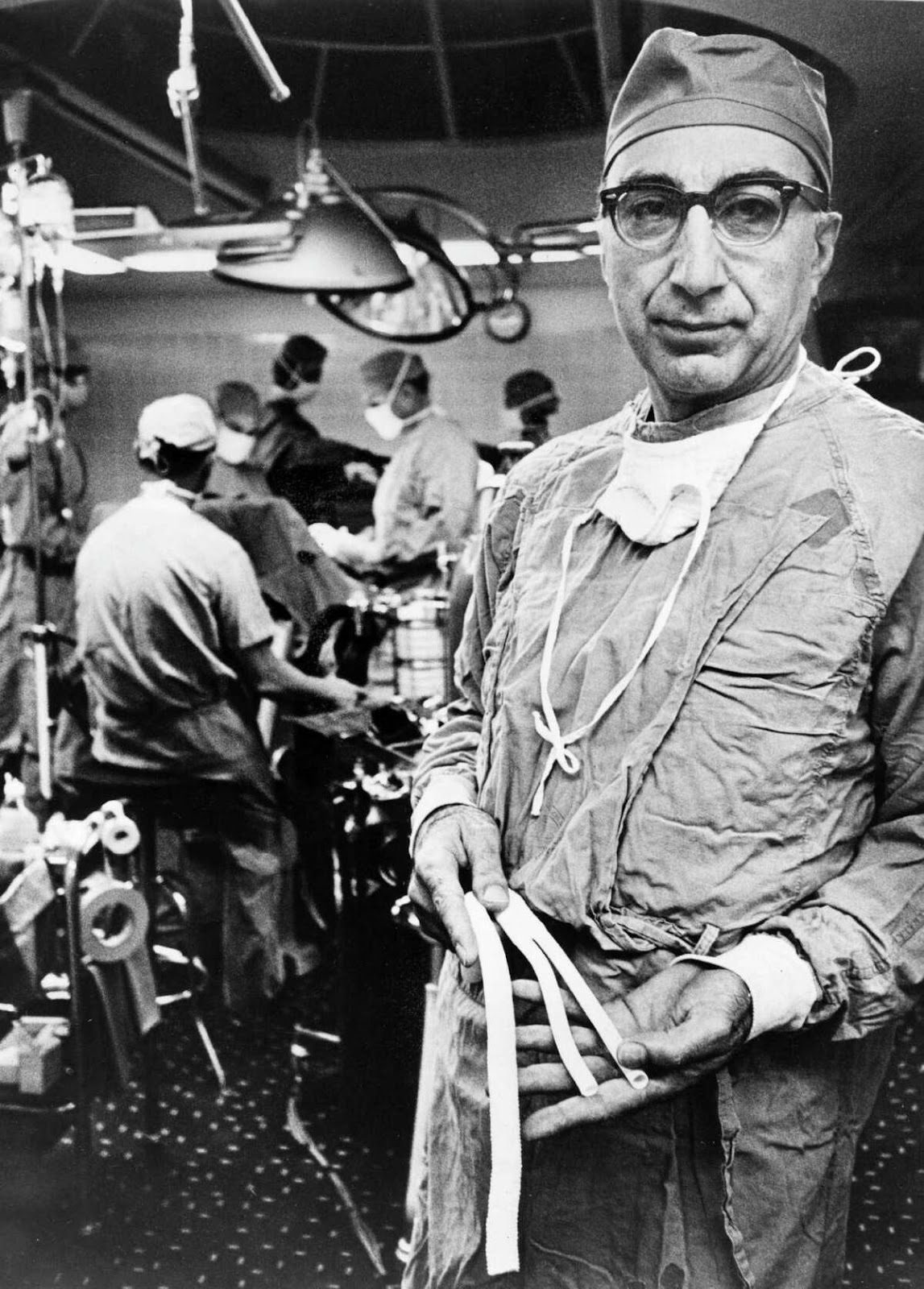

Michael DeBakey’s innovative heart and blood vessel surgeries established him as one of the most influential doctors of the 20th century. He performed coronary artery bypass surgery on patients from all over the world that had problems with their necks, legs and hearts. He had a key role in establishing Houston as a major center for heart surgery and research, as well as in establishing Baylor College of Medicine as one of the country’s greatest medical educational and research institutions.

DeBakey also established himself as a pioneer in the development of mechanical devices to assist people with heart disease. The doctor practiced surgery until he was 90 years old. Throughout his career, he conducted over 60,000 procedures and taught thousands more surgeons. Learn more about his journey at i-houston.

Childhood and versatile development

The future genius was born on September 7, 1908, in Lake Charles, Louisiana, to a family of Lebanese immigrants. His father operated a number of pharmacies, while his mother taught sewing classes. Michael grew up with a brother and three sisters. Both parents fostered in their children a love of study and discovery, as well as outstanding self-discipline and the ability to empathize.

Michael had various interests as a youngster, including biology, literature, French and German. Also, he played saxophone, grew vegetables in his father’s garden, disassembled and assembled machine engines, as well as knitted and sewed. He grew interested in medicine thanks to his acquaintance with doctors who visited his father’s pharmacy, where the boy worked after school.

Medical education

In 1928, DeBakey enrolled at Tulane University (New Orleans, Louisiana), where he completed a two-year course in pre-medical care. During his studies, the young man worked part-time in surgical laboratories. It was this experience that prompted him to choose an academic medical career. Michael was encouraged to specialize in surgery by mentors Rudolph Matas and Alton Ochsner.

In 1932, Michael received his Ph. D., and in 1933-1935, he completed an internship at Charity Hospital in New Orleans. After conducting research on stomach ulcers, DeBakey received a master’s degree. He continued his surgical education in Europe, specifically at the Universities of Strasbourg and Heidelberg. After returning to the United States in 1937, he enrolled at Tulane University and married nurse Diana Cooper. The couple had four sons.

Working with the military

From 1942 to 1946, DeBakey served in the Surgical Consultants’ Division in the Office of the Surgeon General of the Army, where he and his colleagues examined the US Army’s European medical operations and devised strategies to improve surgical services. To aid injured soldiers who were close to the front line, DeBakey established auxiliary surgical teams. They later became divisions of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital, which provided invaluable assistance throughout the conflicts in Korea and Vietnam.

After the end of World War II, DeBakey assisted in the coordination of medical units to accept veterans. He spent several years in Washington, where he served in the Medical Task Force of the first Hoover Commission. This service was engaged in improving the efficiency and effectiveness of state programs. In 1946, the medic returned to work at Tulane University.

DeBakey was also a crucial figure in the establishment of the National Research Council’s Medical Follow-up Agency, which was founded in 1946 to study the health of veterans.

Career in Houston

In 1948, DeBakey was invited to lead the Department of Surgery at Baylor University College of Medicine in Houston. DeBakey agreed despite the fact that this department did not have a training hospital at the time. During his first several years in Houston, he organized surgical residencies at local hospitals, revised the medical curriculum, established surgical research laboratories, sought financing for the medical school and hired qualified staff and faculty members.

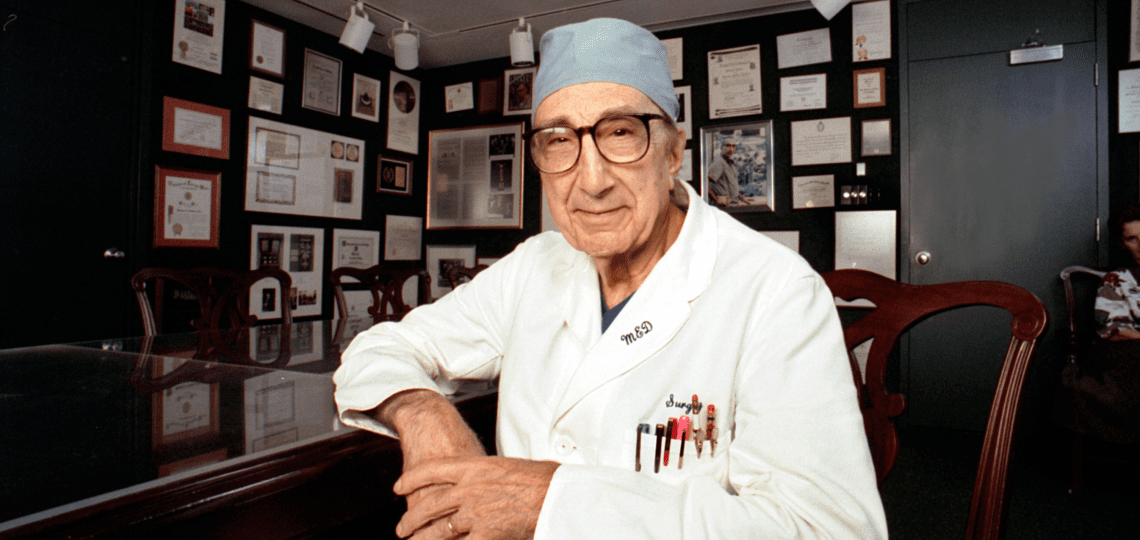

In 1968, the college separated from Baylor University to become Baylor College of Medicine. DeBakey served as its chairman, president and chancellor over the years, continuing to hold the position of head of the Department of Surgery until 1993.

Expert and innovator

While still a student, DeBakey invented a roller pump for blood transfusions. It later became the primary component of the heart-lung machine, which replicates the functions of the heart and lungs during surgery, providing oxygen-rich blood to the brain. It paved the way for open heart surgery.

Some of DeBakey’s surgical innovations and observations were initially ridiculed by the scientific community. While working at Tulane University in 1939, DeBakey and Dr. Alton Ochsner discovered a connection between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. Many well-known doctors were opposed to this idea.

At the same time, the surgeon’s research was unaffected by the skepticism of colleagues. DeBakey’s pioneering ways of surgical treatment of cardiovascular diseases made him the world’s most famous surgeon at one time. In 1952, he and Denton Cooley were the first Americans to successfully repair an abdominal aortic aneurysm by removing the dilated part of the vessel and replacing it with a piece of preserved cadaveric aorta.

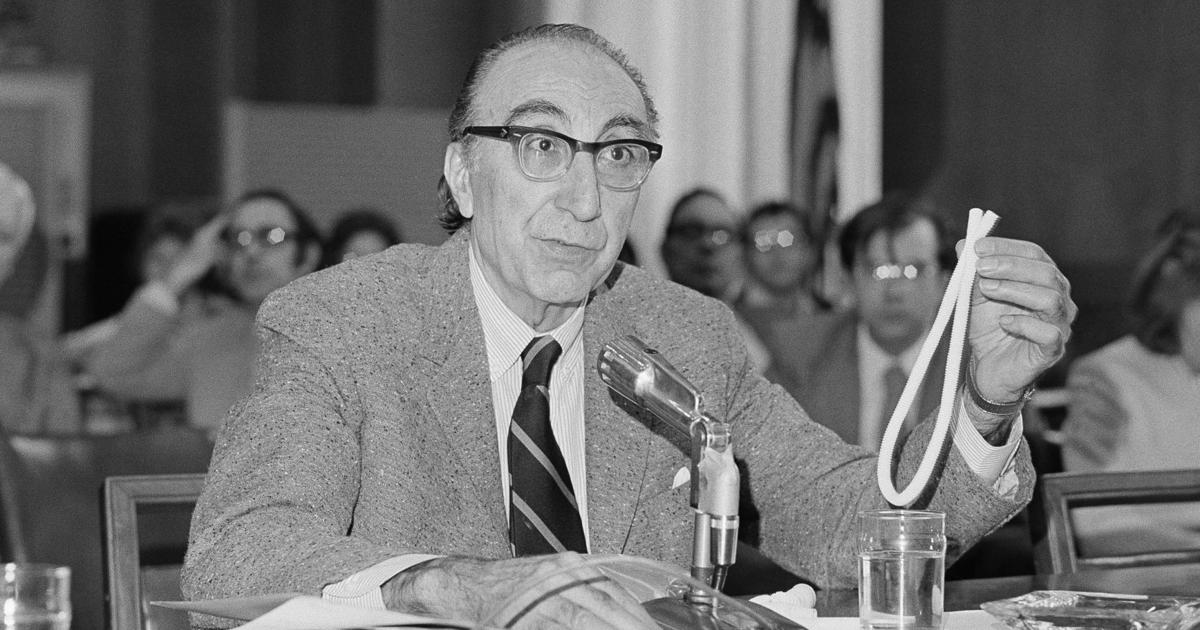

Baylor College of Medicine developed the Dacron graft, which replaces blood vessels (Dacron is a sort of synthetic fiber). DeBakey performed the first transplant with a Dacron graft in 1952. More specifically, he removed an aortic aneurysm (expansion) close to the stomach and replaced it with a Dacron graft. Aneurysms and ruptured aortic walls were nearly always lethal by this point. After some time, DeBakey assisted in the development of a unique knitting machine for manufacturing Dacron grafts.

When they first became available in the 1950s, DeBakey and his colleagues were among the first to utilize coronary artery bypass surgery devices during open heart surgery. DeBakey also, for the first time in the world, devised a technique for treating aneurysms and performed carotid endarterectomy (a surgical procedure to restore impaired blood flow in the carotid artery) and angioplasty with a patch-graft (a procedure for dilating or repairing narrowed or blocked blood vessels). In 1964, he performed the first successful coronary bypass surgery (a heart operation that restores normal blood circulation to the myocardium) and four years later, the first multi-organ transplant.

Michael earned a reputation in the operating room for being a demanding perfectionist while being calm and attentive to patients and their families. The surgeon made postoperative visits till late at night on a regular basis. Even in his 90s, DeBakey got up at 5 a.m. every day, worked for two hours in his office and then proceeded to the hospital, where he stayed until approximately 6 p.m. After lunch, he went back to his library.

Michael was also involved in surgical research, the creation of complete and partial mechanical hearts and the development of cardiac assistance devices. He was the first to successfully implant a left ventricular bypass pump in 1966. At the same time, his permanent mechanical heart replacement prototypes have not been tested on humans. During the 1980s and 1990s, the surgeon worked with NASA engineers to develop the DeBakey VAD, a miniature ventricular assist device with axial flow.

In 1972, DeBakey’s wife Diana died. The doctor’s second love was German actress Katrin Fehlhaber. In 2006, the doctor suffered an aortic aneurysm. Michael was operated on by surgeons he trained himself, using his own surgical technique. DeBakey died of natural causes in 2008, just a few months before his 100th birthday, leaving behind an incredible legacy of surgical innovation and research.