In the mid-19th century, Houston’s horizon barely appeared amidst the swamps and meadows upon which the city was founded. In 1837, it was chosen as the temporary capital of the newly established Republic of Texas, with plans to become a center of trade and political power. Nothing seemed to stand in the way of Houston’s growth—except yellow fever, a then-mysterious virus that struck without warning, killing one in five of its victims.

For 30 years, the disease remained deadly for hundreds of residents until Houstonians learned to combat its epidemic outbreaks. In a way, the illness and measures taken against it played a role in shaping the city. Read more on i-houston.

What Is Yellow Fever?

Yellow fever is an illness that strikes suddenly, characterized by high fever, severe systemic toxicity, a thrombohemorrhagic syndrome, liver damage leading to jaundice, and kidney failure.

The disease derives its name from jaundice, indicating liver failure that turns the skin yellow. For decades, yellow fever caused mass panic, taking lives swiftly, concentrating deaths in just weeks, and bringing commercial operations to a halt. While other diseases, including tuberculosis and smallpox, claimed more lives, yellow fever induced a unique terror due to its severe effects and prolonged mystery surrounding its cause. People only knew it thrived in summer, retreating with the first frost.

Yellow fever was first clinically described in 1648 by Spanish monk López de Cogolludo during an epidemic on Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. The virus spread to North America during the Atlantic slave trade, when infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes laid eggs in water vessels and cotton bales on ships, biting and infecting enslaved people.

A mild case of yellow fever resembles the flu, with symptoms lasting about a week, including fever, chills, muscle pain, and nausea. Symptoms quickly escalate to dangerous fevers, jaundice, and coagulation issues, causing bleeding from gums, nose, and stomach lining. Kidney failure leads to death within one to two days.

The Start of the Epidemic in Houston

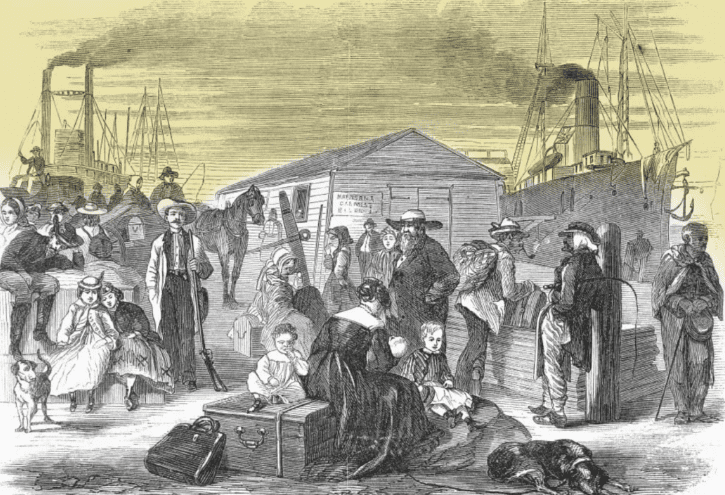

From 1693, yellow fever spread from the Caribbean to the U.S. Gulf Coast. It reached the Gulf of Mexico in the 1830s, with local mosquitoes transmitting the disease from infected to healthy individuals. Mosquitoes breed in freshwater, making the bustling Gulf Coast port cities—filled with people, water containers, and ships stocked with tropical fruit—the ideal environment for yellow fever’s spread.

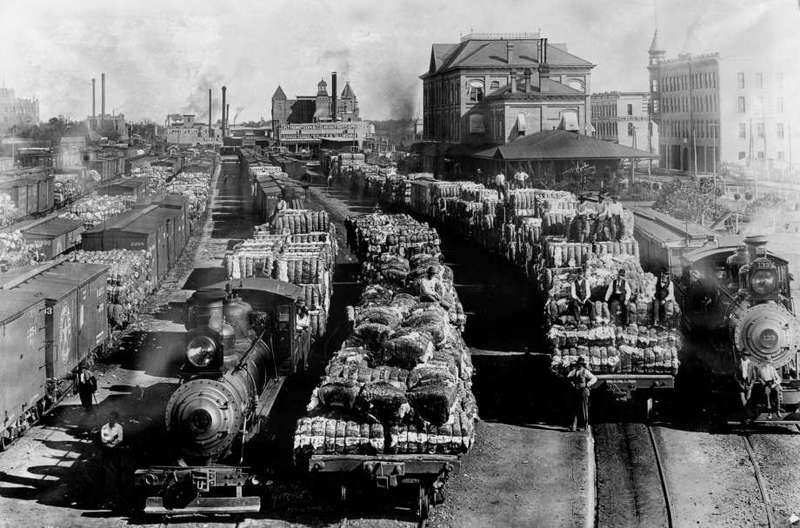

In summer 1839, two years after Houston was named the capital of the Republic of Texas, the city experienced its first outbreak of yellow fever. The disease, initially impacting the cotton industry and railways, spread from Indianola and Galveston to Houston, soon leaving bodies accumulating in the streets.

At the time, no one knew that mosquito bites spread the illness, so doctors instructed Houstonians to try various methods to halt the virus. Residents attempted to “clean the bad air” by burning tar and sulfur. When these efforts proved futile, cannons were fired, hoping the force would expel the illness. A physician from Galveston, Ashbel Smith, even swallowed vomit from infected patients to see its effects but did not contract the disease.

People died so rapidly that they were buried in long trenches without ceremony. Before winter arrived, the epidemic had killed one-twelfth of Houston’s population. The cold months slowed the disease’s spread, but by summer 1843, yellow fever returned, as it would for another 30 years.

The Deadliest Year

In 1867, with a population of 6,000, Houston became Texas’s military center due to an increasing influx of federal troops stationed there during the Reconstruction of the South—a period after the Civil War, from 1865 to 1877. That summer, yellow fever killed 492 Houstonians. People of all social classes were buried hastily outside the city, including the widow of Sam Houston, the first and third president of the Republic of Texas.

This deadly outbreak affected citizens across social classes. According to a 14-year-old Galveston resident, soldiers “died like flies on paper.” Of 72 soldiers stationed in Houston, 71 became infected, and 25 of them died.

Anti-Epidemic Measures

When the epidemic returned to Galveston Island in 1870, Houstonians were prepared. They imposed a strict armed quarantine, barring infected islanders from entering Houston. From then on, each time yellow fever reached the island, the city enforced quarantine to curb the spread of the deadly disease.

At the turn of the 20th century, Houston had evolved into a commercial hub. The city installed advanced drainage systems. With new roads, ditches, and channels, Houston lifted itself out of the swamp, making it harder for mosquitoes to harm the population. Yellow fever thus catalyzed the city’s rapid development, including its underground communications infrastructure.

Identifying the Cause and Vaccine Development

The theory that yellow fever was transmitted by mosquitoes gained traction with each new death. In 1900, U.S. Army doctor Walter Reed conducted studies to verify Cuban epidemiologist Carlos Finlay’s theory that Aedes aegypti mosquitoes spread the disease.

Reed confirmed this theory, and following his death, Major William S. Gorgas, a doctor and friend of Reed’s, led a campaign to eradicate the mosquitoes in Havana, Cuba’s capital. Efforts to destroy mosquito breeding grounds, quarantine patients behind mosquito nets, and other measures set an example for other cities. Yellow fever, from its appearance until 1905, not only brought illness and death but also intensified city rivalries and created financial difficulties.

Although Texas experienced another yellow fever outbreak in 1905, cities in the state soon took measures to purify water and implement sanitation practices modeled on Houston’s example. These cleansing protocols continued into the early 21st century, with isolated cases still being reported worldwide.

The yellow fever vaccine was developed in 1937 by Max Theiler, a South African virologist and doctor who became the first African Nobel laureate. After transferring the yellow fever virus to lab mice, Theiler found that the weakened virus provided immunity to rhesus macaques, leading to the creation of a human vaccine.

Max Theiler