In 1967, South African surgeon Christiaan Barnard performed the world’s first human heart transplantation. Two years later, Houston-based cardiac surgeon Denton Cooley executed the first total artificial heart implantation. On that day, Cooley became the face of the world’s cardiac surgery, but he also sparked one of the biggest disputes in the history of American medicine.

At his peak, Cooley was the busiest cardiac surgeon in the United States, performing up to 12 procedures each day as if working on a conveyor belt. Patients were assigned to separate operating rooms, where junior doctors opened their breasts and exposed their hearts. Then Cooley dashed between operating rooms to complete the most essential part of each operation. Some criticized his work as being of poor quality, while others equated Denton with absolute medical excellence. Find out more about how a University basketball star became a legend in the world of cardiac surgery at i-houston.

Education

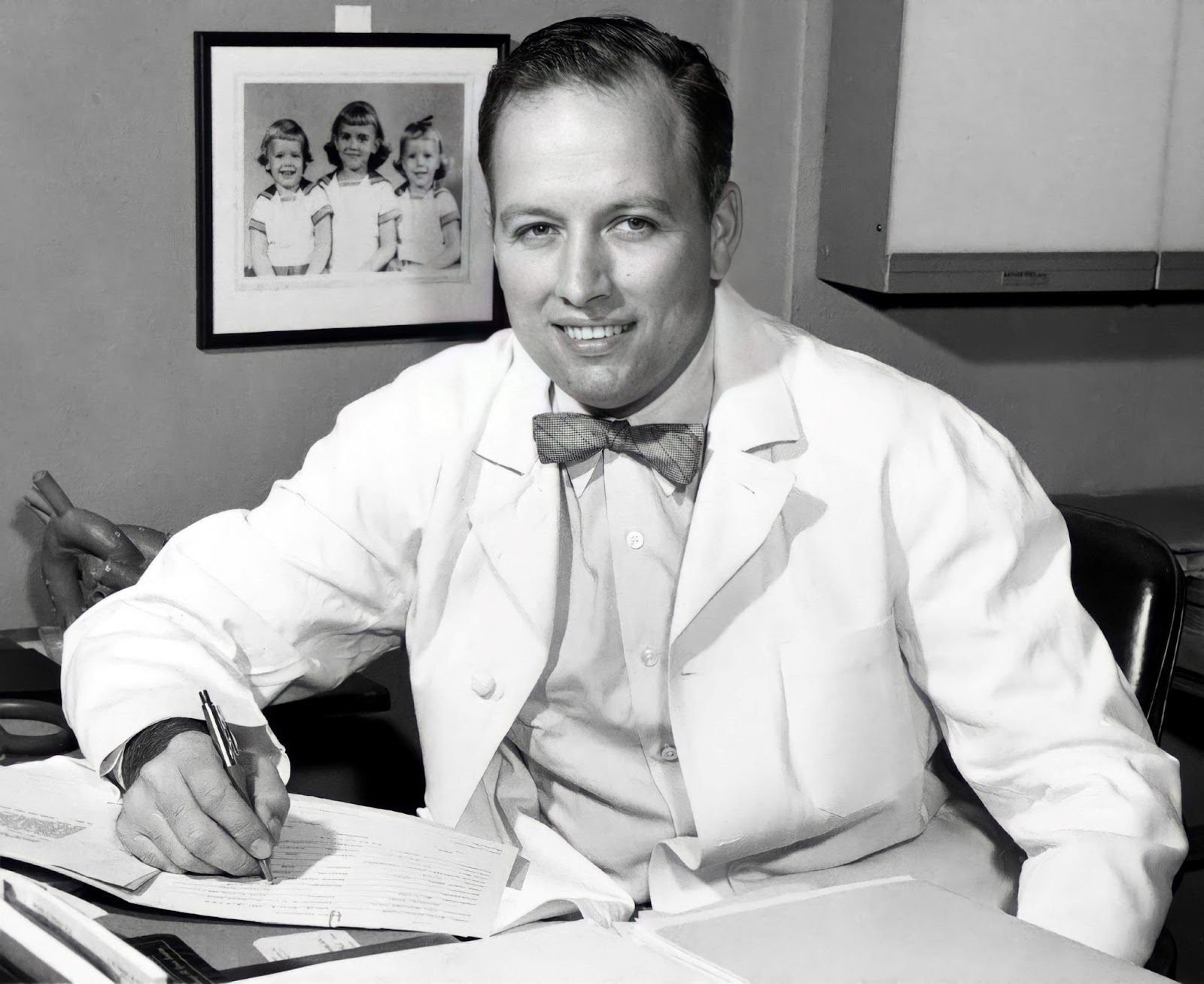

Denton Arthur Cooley was born on August 22, 1920, in Houston to a wealthy family. His father was a prominent dentist. Denton was shy and insecure as a child. Everything changed when the youngster began to succeed in his studies and sports, in particular, he played tennis and basketball.

After high school, he entered the University of Texas (at Austin) to study zoology. At the University, the young man excelled on the University’s basketball team. At first, he intended to join his father’s dentistry practice, but at the age of 17, he became interested in surgery. The boy was inspired by a visit to an emergency room in San Antonio and witnessing the process of patching up stab wounds.

He soon transferred to the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland. Denton’s medical education was funded in part by the army training program. In 1944, he got his degree and continued to work as an intern at the same university.

First steps in medicine

In 1944, pediatric cardiologists Alfred Blalock and Helen Taussig developed a surgical procedure for treating methemoglobinemia, also known as “blue baby syndrome,” a condition of elevated levels of methemoglobin in the blood. That same year, Cooley assisted Blalock in correcting a congenital heart defect in a child with methemoglobinemia.

Inspired by Blalock, Denton decided to specialize in cardiovascular surgery. Even as an intern, Cooley astonished his colleagues with his unusual speed and agility in the operating room, which he attributed to his athletic background.

In 1946, Cooley joined the Army Medical Corps. He was the chief of the surgical service at the station hospital in Linz, Austria, and retired in 1948 with the rank of captain.

After graduating from a residency at Johns Hopkins University, he stayed there to teach surgery. In 1950, he moved to London to study under the renowned British surgeon Russell Brock. In 1951, he was appointed associate professor of surgery at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. In 1962, Denton established the Texas Heart Institute, where he became chief surgeon seven years later.

Surgical innovations

Denton Cooley worked in an era when doctors could design their own devices and tools and use them on patients without outside supervision. At the time, there were no human experimentation committees. As a result of working in such an innovative context, Cooley has created a number of commonly utilized cardiovascular procedures and devices. He and his colleagues, for example, invented artificial heart valves. Between 1962 and 1967, the death rate of patients following valve transplantation fell from 70% to 8%.

Denton is also the creator of a technique for reducing the amount of blood transfused in the heart-lung machine, which “breathes” for the patient during open heart surgery. This approach lowered the occurrence of infections like hepatitis B. The invention was truly revolutionary because there was no vaccination to prevent a severe and potentially fatal liver infection at the time. It also made it easier to operate on patients who refused blood transfusions owing to religious beliefs.

Denton’s other contributions to medicine include the first successful carotid endarterectomy (an operation performed to restore impaired blood flow in the carotid artery), as well as methods for repairing diseased heart valves, congenital heart defects and aortic and ventricular aneurysms. In his entire life, he performed about 115,000 open heart surgeries.

Heart implantation and conflict with DeBakey

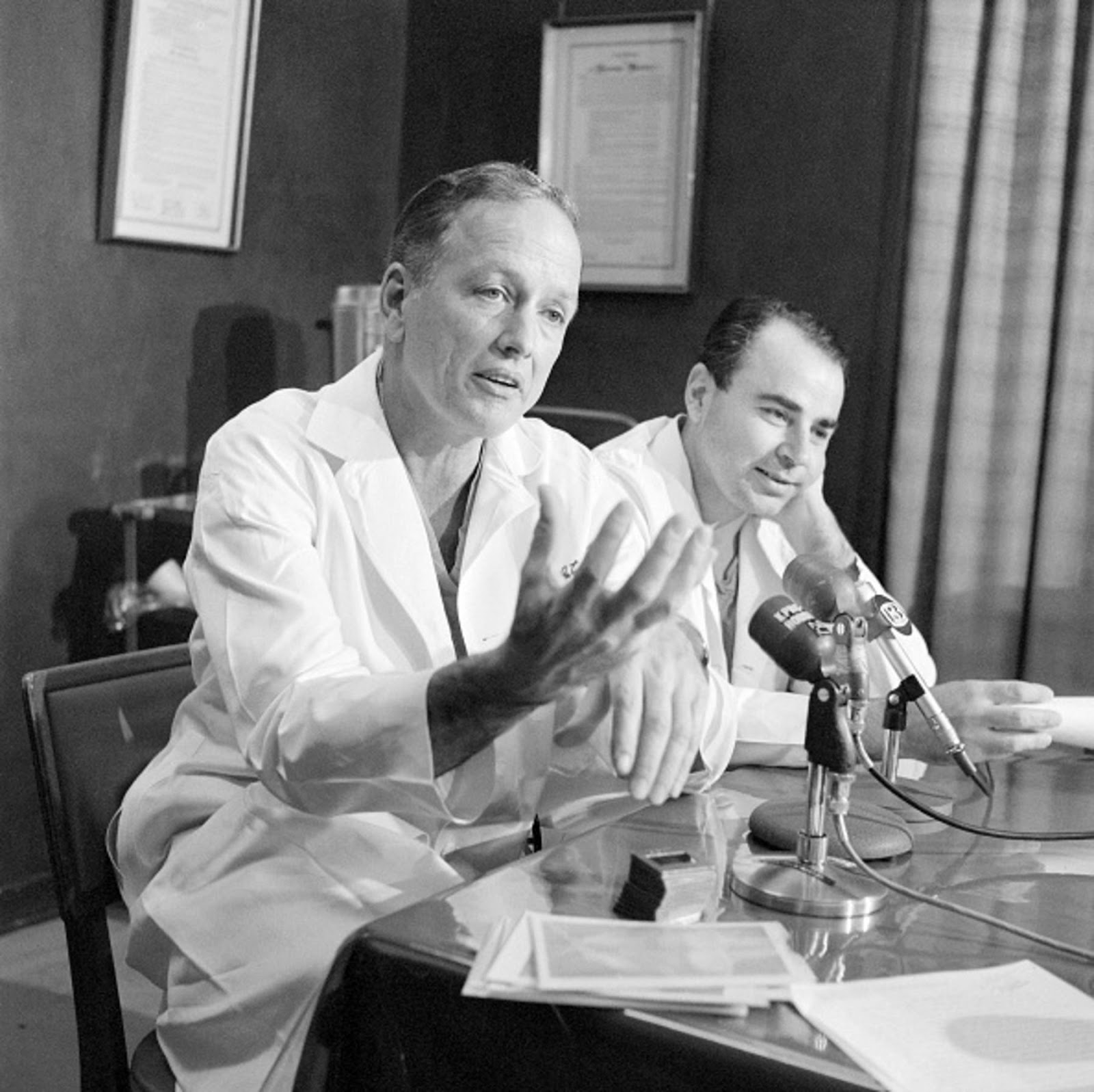

In the 1950s, Cooley began working with Michael DeBakey, a pioneer of Houston cardiothoracic surgery and one of the most prominent doctors of the 20th century. The 60-year partnership between Cooley and DeBakey has brought both men great triumphs and failures.

The first disagreements arose when DeBakey began working on a cardiopulmonary bypass device to immobilize the heart during surgery, but it was Cooley’s design that was successfully used at the Methodist Hospital at Baylor College of Medicine in 1955.

Due to temperamental differences, the two outstanding surgeons found it difficult to communicate, therefore Cooley shifted his practice from Methodist Hospital to St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital in 1960. At the same time, he worked at Texas Children’s Hospital and taught at Baylor College of Medicine, which is why he was in constant contact with DeBakey.

The latest heart and blood vascular surgery techniques of two doctors helped tens of thousands of patients. These accomplishments, however, were overshadowed on April 4, 1969, when Cooley, working independently of Dr. DeBakey, executed a pioneering artificial heart implant without his authorization. It was a half-kilogram device composed of plastic and Dacron that was connected to the control panel by the bed through tubes.

At the time, Dr. DeBakey and the medical team at Baylor College of Medicine were only working on developing an artificial heart. DeBakey argued that the device, which had been tested on calves, was not yet ready for human testing, but Cooley decided otherwise.

DeBakey felt betrayed since his own protégé had turned out to be his greatest opponent. This was the world’s first successful implantation of an artificial heart in a human. Cooley, according to DeBakey, committed an unethical and childish act. Furthermore, he argued that by utilizing an unfinished device, he violated federal regulations and compromised federal research funding at Baylor College of Medicine.

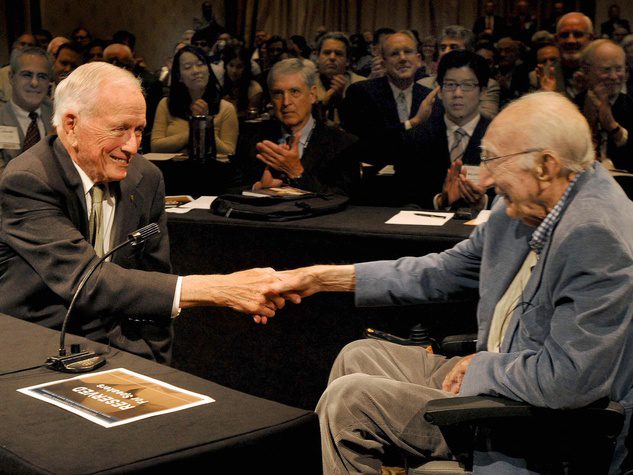

So began a 40-year conflict that revealed the identities and ambitions of the two surgeons and ended just a year before the death of 99-year-old DeBakey in 2008. Cooley spent a lot of time explaining his actions in terms of his medical duty to do all possible to save the patient’s life. The patient, by the way, was 47-year-old Haskell Karp from Illinois. Later, also Cooley stated that the operation was a gesture of patriotism because he did not want the Russians to be the first to implant a completely artificial heart and get ahead of the US.

The artificial heart worked for 64 hours, which was longer than during animal tests. At the time, the quest for a donor heart was still ongoing. When it was finally found, Cooley performed an operation. Mr. Karp was kept alive by the new heart for another 32 hours until he died of pneumonia.

Cooley later resigned from Baylor College of Medicine, and the American College of Surgeons convicted him of unauthorized use of the device. As DeBakey was presented with a lifetime achievement award from the Denton A. Cooley Cardiovascular Surgical Society, Cooley left the stage and knelt next to DeBakey, who was sitting in a motorized scooter. They exchanged hearty handshakes.

Denton himself retired from surgery on his 87th birthday but remained involved at the Texas Heart Institute as honorary president. The renowned heart surgeon passed away on November 18, 2016, at the age of 96.